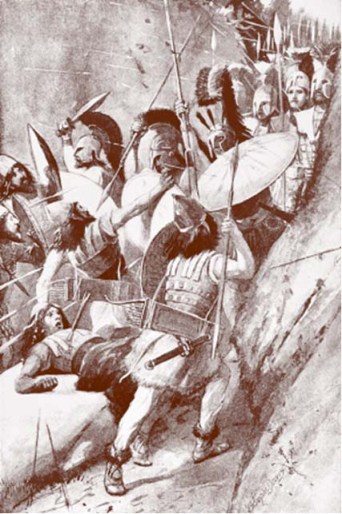

A memorial of the great Battle of Thermopylae in Greece depicting King Leonidas. (Credit: Mino Surkala)

A massively outnumbered Greek force faces off against an invading Persian army in a fight to the death that has echoed down through the ages.

The hopeless band of heroes facing off against a much superior force is one of the most captivating tropes in storytelling.

And perhaps no better example of this archetype exists than the Battle of Thermopylae, one of the first such battles in recorded history.

The Battle of Thermopylae movie, best known today as "300: Rise of an Empire," was a three-day battle in 480 B.C. between a small group of Greek soldiers and the huge Persian Army.

The Greeks lost, which isn't much of a spoiler. However, the battle's values of sacrifice, courage, and patriotism have endured to this day, owing to the sacrifice, bravery, and patriotism it represented.

It's also a powerful example of an outmanned force using military and tactical advantages to inflict a heavy toll on their adversary. Throw in a dash of arrogance, betrayals, and eminently quotable speeches, and you've got the makings of a fantastic plot.

A Battle for the Ages

A few ancient Greek historians, including Herodotus, the "Father of History," have contributed to our understanding of the Battle of Thermopylae.

Their accounts are fairly consistent, though they differ on a few minor details. The recent archaeological study, such as the discovery of Persian arrow points, has also contributed to the battle's historical record.

Iron arrowheads and spearheads were discovered on the Koinos hill, where the Thermopyles' last defenders were killed by enemy arrows.

(Credit: Therese Clutario/CC by 2.0/Wikimedia Commons).

Thermopylae is near the coast in the southern part of the Greek mainland. Due to the mountainous nature of much of Greece, the invading Persians were forced to take a non-linear path to the Greek heartland, one that wound its way along the coast.

This path must pass through a narrow pass known as Thermopylae at some stage

In the first place, why was there an occupying army? Part of the response can be found in the failure of the first Greco-Persian war, which ended with the Persian defeat at the Battle of Marathon a decade before.

(It is now popularly called in honor of a spartan who brought the news of victory against Persian in the Battle of Thermopylae).

The Persians were also enraged by the Greeks' support for the Ionian rebellion, which had recently upended the Persian Empire's eastern regions. Xerxes I, the newly elected Persian emperor, agreed to continue his father Darius I's conquest of the pesky Greek city-states.

To do so, the Persians gathered a huge army, drawing troops from all corners of their vast empire. While historical estimates placed the Persian army at a million men or more, more recent estimates put it at around 300,000 men or less — still a sizable force.

The invasion of Greece took four years to plan and required a significant logistical investment. For the hungry troops, supply caches were placed along the route in advance, including large piles of salted meat and grain for the horses.

Xerxes also had a huge canal cut through the isthmus of Mount Athos for his ships, and engineers built a massive bridge across the Hellespont, a narrow canal that divides Europe and Asia (though still nearly a mile wide at its narrowest).

The Persians started their long march from modern-day Turkey, through the Hellespont, and along the northern shore of the Aegean Sea, after completing their preparations. Around the same time, a similarly large Persian navy set sail for Greece.

The Greeks, who had been keeping a close eye on the Persian belligerence, realized they stood no chance against the much greater enemy forces.

In the face of what they realized was a mutual existential threat, the usually antagonistic Greek city-states, especially Athens and Sparta, had already formed an unprecedented alliance.

They came up with a strategy: if they could force the Persians to fight them in places where the Greeks had territorial advantage, they might be able to win. Thermopylae's pass was an obvious decision.

(Credit: Bibi Saint-Pol/CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons)

The pass was the only direct route open to an army intent on conquering the Greek homeland, as it was situated where steep mountains ran almost to the sea.

The Persians couldn't put their full force to bear on an enemy because it was narrow enough (perhaps a few hundred feet at the time), so the outnumbered Greeks could meet them on an equal footing.

Current Phoenicians-built fortifications provided an additional layer of protection. An army of around 7,000 Greeks, led by Spartan King Leonidas, decided to make their stand here.

A Doomed Struggle Begins

According to Herodotus, the Persians waited four days after arrival at the pass before attacking. During this time, Xerxes sent an envoy to the Greeks, asking them to lay down their weapons and retreat peacefully. “Come and take them,” Leonidas replied, according to historians.

The Persians invaded on the fifth day. A wave of soldiers pounced on the Greeks, who had formed themselves in a traditional line in the pass: A phalanx of spearmen with overlapping heavy shields.

(Credit : John Steeple Davis/Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

The Greek tactics, wedged into the narrow pass, proved devastatingly successful. They repelled the first wave of attackers, as well as the second squad of Persian warriors known as the Immortals.

Xerxes stood up three times during the battle, afraid for his life as he watched his best soldiers die in droves, according to Herodotus.

The following day's combat went a little better, though Xerxes is said to have sentenced any soldier who fled from their position to death.

While resisting the Persians' best attempts to break through their line, the Greeks suffered few defeats.

Their superior armor and long spears, along with military tactics tailored to the terrain they defended, most likely helped them gain the upper hand.

On the second night, however, a betrayal sealed the Greeks' doom. A local shepherd offered to show the Persians a mountain path that could be used to circumvent the Greeks and strike from behind in exchange for a reward from the Persian king.

Xerxes dispatched a fleet of men under the command of Hydarnes right away. By morning, the troops had marched through the night and were ready to attack the Greek positions.

As Leonidas became aware of the Persians' movements, he made a hasty decision. Faced with a near-certain defeat, he dispatched the majority of his troops.

A small contingent, including Leonidas, would remain at the pass to guard it and keep the Persians at bay for as long as possible.

The 300 Spartans, as well as Thessalian and Theban soldiers, were among the remaining men. They were possibly about 1,500 men in total.

Xerxes launched his final attack around mid-morning, according to Herodotus' The Histories. In a classic pincer maneuver, Persians closed in from both ends of the pass.

Outmanned and facing imminent defeat, the Greeks “displayed the greatest strength they had against the barbarians, battling recklessly and desperately,” according to Herodotus.

The Persians, aided by whips from behind, assaulted and slaughtered a large number of people.

However, in the end, the sheer force of numbers triumphed. Leonidas was killed, and the few remaining Greeks fled to the pass's narrowest point to make one last stand.

“They defended themselves with swords, and with their hands and teeth in that drastic situation. “The barbarians started rain of arrows those almost buried them with piles of arrows.

Some Persians were attacking from the front by destroying the defensive wall make them helpless, while others encircled them on all sides,” Herodotus writes.

The Spartans and Thessalians were nearly all killed, while the Thebans surrendered after realizing their defeat.

Remembering Thermopylae, despite their loss at Thermopylae, the Greeks would eventually win the second Greco-Persian war, but not before the Persians sacked Athens.

Xerxes fled to Asia after a naval defeat at the Battle of Salamis, losing many men to disease and starvation along the way. He left a force to continue the invasion the following year, but they were also unsuccessful.

The Battle of Thermopylae was not really a decisive moment in the Greco-Persian war from a strategic perspective. Later wars, such as Salamis, which shattered the Persian fleet, would prove more important.

When it comes to sheer drama, however, the Battle of Thermopylae is unrivaled. It symbolized the battle of a smaller Greek empire against an overbearing power intent on stealing their homeland, and it forever enshrined the Spartans' valor.

Despite the Greeks' defeat, the war served as a symbol of independence over tyranny and bravery over fear. Its allegorical forces have only grown stronger over the past 2,00 years.